What I love about the sky above Budapest is that I can see it.

There are strict limits on the height of buildings in Budapest. Traditionally, they could not be build taller than Parliament or Saint Stephen’s Basilica, both of which are 96 meters tall. There was symbolic value to this choice: it emphasized the importance of government and religion, as well as their equal contributions to the life of the nation, at least theoretically. In 2018 this tradition was codified — after that year, no buildings could be built over 90 meters, and anything between 65 and 90 meters required government approval. The only exception was the MOL tower, which had already been approved — it was completed in 2022 at a very tall (for Budapest) 143 meters. MOL (Magyar Olaj- és Gázipari Nyrt.) is the Hungarian oil and gas company, so its height is symbolically appropriate: church and government are less important, now, than the interests of fossil fuel. The tower itself rises above the much lower buildings that surround it. One could compare it to the tower of Sauron. It has also, less charitably, together with the “campus” at its base, been compared to — how shall I put this delicately? A certain portion of the male anatomy. Or it could be a raised middle finger, from Buda to Pest. It looks as though it belongs in Frankfurt.

Most of Budapest still consists of old buildings, low enough that you can see the whole sweep of the sky above you. I love looking at it, especially around sunset. When I walk down Rákóczi út, from Blaha Lujza tér to Astoria, I can see the sun setting over the Danube. The whole sky turns pink and orange, and the old buildings bask in that evening glow, becoming even mellower. Then twilight begins to fall. Because I can see the sky, even in the middle of the city I feel connected to something larger, to the natural world of which I am a part. And it’s even more beautiful seeing the sun set while I’m standing on the Szabadság híd (the Liberty Bridge, one of the seven famous bridges of Budapest). Then, you can see the sun setting among pink and orange clouds over Castle Hill, and the green snake of the Danube flowing beneath. You can think — at least I always think — about the thousands of years during which people have seen the exact same view, before there were bridges over the Danube, while they were built over the years one by one, when they were destroyed by bombs, during my grandmother’s lifetime, my mother’s . . . and now mine. Seeing the sky in that way places me geographically as well as in time. It makes me feel grounded as well as — what do we call grounded in time? It reminds me of my place in the scheme of things. It gives me a sense of my possibilities and limitations as a human being.

I mean no disrespect to other cities, not even Frankfurt. But Budapest, more than any other city I have been to, feels as though built on a human scale. (With the exception of the MOL tower, but then the fossil fuel industry, which reaches back into the time of the dinosaurs, bringing forward energy laid down in the earth long ago, is not in fact on a human scale, it is?) And it seems to me that we need the human scale now, more than ever.

I suppose the reason I’m writing about this is that in my lifetime, everything seems to have gotten larger. The beautiful old skyline of New York, already probably too high and aspirational for human beings, now feels as though constructed to be demolished in Hollywood superhero franchises. Its tall glass towers feel appropriate for supervillains, while all the interesting life (in my opinion) happens at street level, the level of the parks and little bodegas. The old corporations I remember were bought by larger corporations, and now it feels as though every industry is dominated by approximately five major entities. Yet interesting human life continues at street level — beneath the five major publishers are ecosystems of smaller independent publishers releasing some of the most innovative books of our time. I suspect the same thing is happening in other media, in music and art. At least when the larger entities don’t strangle the smaller ones, as they currently threaten to do with the rise of AI, which steals all media to create its own ubiquitous sludge.

What I want to argue here is that we need the human scale, and we should actively choose the human scale. It’s hard, now — I recently ordered some used books from AbeBooks, feeding the Amazon beast. It’s almost impossible to escape this era of hyper-conglomerization. But I would like to.

I would like to make the argument that the human is fundamentally important, and that even before the advent of AI, we were in danger of losing sight of humanity. We created buildings and cities that made us feel insignificant, rather than expanding our souls. When I am in a forest or a cathedral, it feels as though my human soul takes flights. Even the older buildings of New York can do that. But walking beneath the glass towers of London’s financial district just makes me feel small, and somehow excluded. They seem to belong to people who arrive in helicopters and shop at stores that were once associated with a specific human creativity but are now themselves just parts of large conglomerates, such as Dior and Chanel.

I suppose what I believe, or perhaps want to believe, is that creativity always happens down in the streets, at the human level. It happens among people who are not particularly powerful, who are scrambling to make ends meet and create literature, art, and music that might endure. From that level it rises up, but perhaps not all the way to the top of the Gherkin or MOL tower. Perhaps the highest it can go is 96 meters, at least in Budapest.

When I was in my 20s, I worked at a corporate lawyer in the MetLife Building above Grand Central Station. Every day, I rode the elevator up to the 42nd floor and went into my small office, which had a view of the city. There, I spent my days in billable 15-minute increments, helping large corporations make more money. I left for the human scale of a PhD program studying literature, teaching students in run-down classrooms. I still work at that human scale (the classrooms are still run-down). Teaching is changing — the university is also being invaded by the corporatification, the AI-ification, of everything. But I will hold on to the human scale as long as I can. Unless we are taken over by the machines, I suspect that will be the rest of my lifetime.

Hopefully, the sky over Budapest will remain as visible as it as now, for as long as my own human life — for as long as I can see it, walking down Rákóczi út.

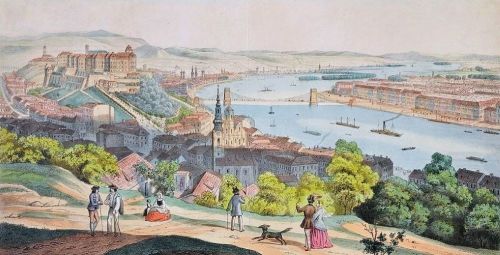

(The image is a nineteenth-century engraving of Budapest.)

❤

Being in Nature – even in my small patio – and interacting with the cats keeps me human.