Two weeks ago, I went to the symphony with our teaching team — four faculty members and seventy-two students. We heard a modern piece, which happened to be a very good modern piece — I’m not always fond of modern classical music, but this was lovely, like being under water and seeing aquatic creatures all around you, jellyfish floating, fish flashing by, even whales passing like shadows underneath. And then Mozart, and then Tchaikovsky. So it was a bit like traveling from the twentieth to the eighteenth and then to the nineteenth centuries through music. The students enjoyed it — I was not sure they would, but many of them have grown up playing musical instruments, and they all seemed to like the music, as well as the physical act of going to the symphony, sitting in that magnificent hall, and just listening for a while.

At the end of the symphony, my left eye was bothering me. I was seeing something — like smudges? Or bits of string? I thought, I must be tired . . . I went home, and then to sleep.

The next morning I woke up, and the smudges and bits of string were still there. Then, when I closed my eyes, I saw something new — flashes of light. I was frightened, of course. You’re not supposed to see things when you close your eyes, certainly not flashes of light at the periphery of your vision. My first thought was to ask Dr. Google what was going on. Dr. Google told me that I might have retinal detachment, in which case I would need surgery within the next 72 hours. He’s great at scaring you, Dr. Google.

I had three things to do that day: a meeting, a lecture, and a presentation. But the first thing I did was go to my optometrist’s office, which luckily is close by. The sign said it would not open until 10:30, so I went to the bookstore and bought the complete poems of Stevie Smith, because what else do you do while you’re waiting for the optometrist? At 10:30 I went back and spoke to the receptionist, who said that he was on vacation in Gibraltar, but she would call him for me. The advantage of having an optometrist who has known you for twenty years is that you can talk to him while he’s on vacation in Gibraltar, and he will tell you to look out the window and cover one eye, then the other, and then tell you that you probably don’t have retinal detachment, but you should go see an ophthalmologist to make sure. And by the way it’s been raining all week in Gibraltar, but the weather is nicer today — the sun is shining.

I called and made an appointment with the ophthalmologist for later that day — luckily the eye clinic was able to fit me in. Then I cancelled my lecture, which was at the same time as the appointment with the ophthalmologist, and went to my meeting. From my meeting I took a Lyft to the ophthalmologist, where my eyes were dilated and placed in front of machines, a lot of machines — they all took pictures of my eyes, and then I sat for a while and made small talk with other people there for eye procedures, and then there were more pictures, and then I talked to the ophthalmologist, who told me I did not have retinal detachment, at least not yet, but I did have vitreous detachment, which is a normal thing that happens when you get older, especially when you’re nearsighted. But older in this case could mean in your thirties or in your eighties, there was no particular rhyme nor reason — it was just one of those things that happened. And by the way I had a mild case of lattice degeneration in both eyes, which made this sort of thing more likely. Apparently, however, that isn’t as bad as it sounds, which makes me wonder, as a teacher of rhetoric–if it’s not that bad, why call it “degeneration”? I mean, there are other words in the English language that would not sound so dire!

It’s hard living in bodies, isn’t it?

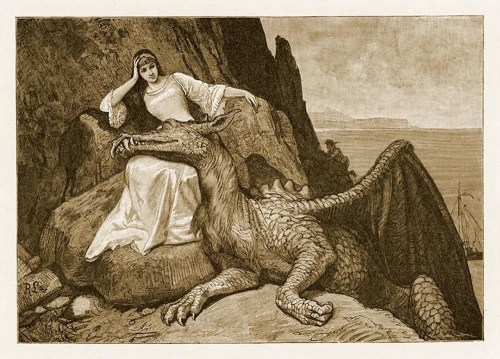

We have to live with all the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, plus all the aches and pains and accidental injuries, the times we stub our toe, the headaches, the arthritis, the heart disease. All the natural shocks that flesh is heir to. And while we live in these mortal bodies, subject to time, there is something within us that endures, that feels immortal. Is it immortal? I don’t know, but it certainly feels that way. I know that objectively I’m getting older, but it’s always a shock to feel anything related to aging, because inside I would say that I’m still fifteen, that I haven’t really changed that much from the teenager who read books about dragons. I am, as a matter of fact, rereading those books about dragons.

And yet, those natural shocks do shake my sense of self. I am not as confident in myself as I was before the thyroid surgery two years ago, which turned out to have been unnecessary. Or the dental stuff to fix a problem with my bite, which is ongoing. Or now this eye thing, which is natural and will likely happen to my other eye as well. There is no cure, by the way — it just gets better by itself over time. It’s starting to feel as though my body is a problem, rather than a miraculous biological phenomenon that allows me to participate in the glorious physical world. That allows me to smell lilies of the valley and taste hot cocoa, and stroke a cat’s fur, and hear the wind in the leaves. I keep worrying that I’m somehow running out of time.

We are such a strange mixture of spirit and flesh, aren’t we? And now along comes AI, that other kind of I. It’s neither spirit nor flesh, but we are asked to believe that it will somehow replace us, that it will outpace us. I’m going to venture a tentative hypothesis: that there is no spirit without flesh, that it is our mortality, our temporal boundedness, which gives us imagination, creativity, the elusive thing we call soul when we see it in a human being or a painting or a poem. (Or a dog’s eyes. Don’t tell me dogs and bats and octopuses don’t have souls. I’m quite sure trees have souls.)

When I open my eyes now, the left one reminds me of my own fragility. What do I do with this knowledge? I knew it before, of course — but more theoretically. Now there it is, in front of my eye, my I. The only thing I can think of, at the moment — the only response that comes to mind — is to make the spirit blaze brighter. However much time I have left, I want to spend it smelling lilies of the valley and drinking hot cocoa and stroking cats and listening to the wind in the leaves and reading (and writing) about dragons.

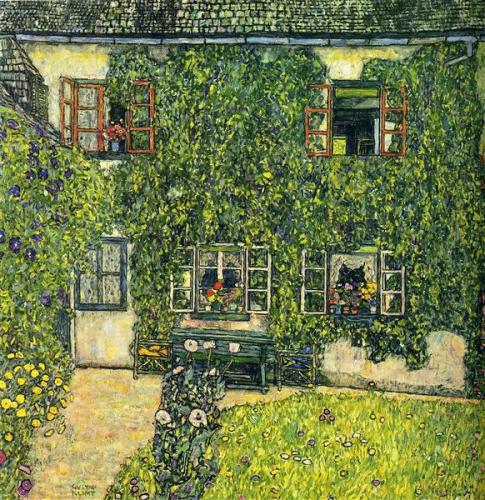

(The image is a miniature painting of a woman’s eye, probably from the 18th century.)